Australia's unemployment rate is 3.5 per cent, and it hasn't been this low since August 1974.

Currently, there are 480,000 job vacancies and 494,000 officially unemployed people.

It equates to almost one unemployed person per vacant job, compared to three times that number before the pandemic hit Australia.

Does this mean we're close to full employment?

What is full employment?

The concept of "full employment" has a fascinating history.

But when policymakers use it today, they're not using the term as it was originally intended.

Australia used to have an official policy of full employment. It was the foundation of our labour market from 1946 to 1975.

During that era, governments kept the unemployment rate below 2 per cent, on average, for nearly three decades.

It coincided with the long economic boom of the post-war years, which saw rising real incomes and vast improvements in the standard of living, and rapid growth in affordable housing.

But interestingly, the people who provided the intellectual foundations for the policy argued amongst themselves about what "full employment" should mean.

And it's worth reading how they thought about things.

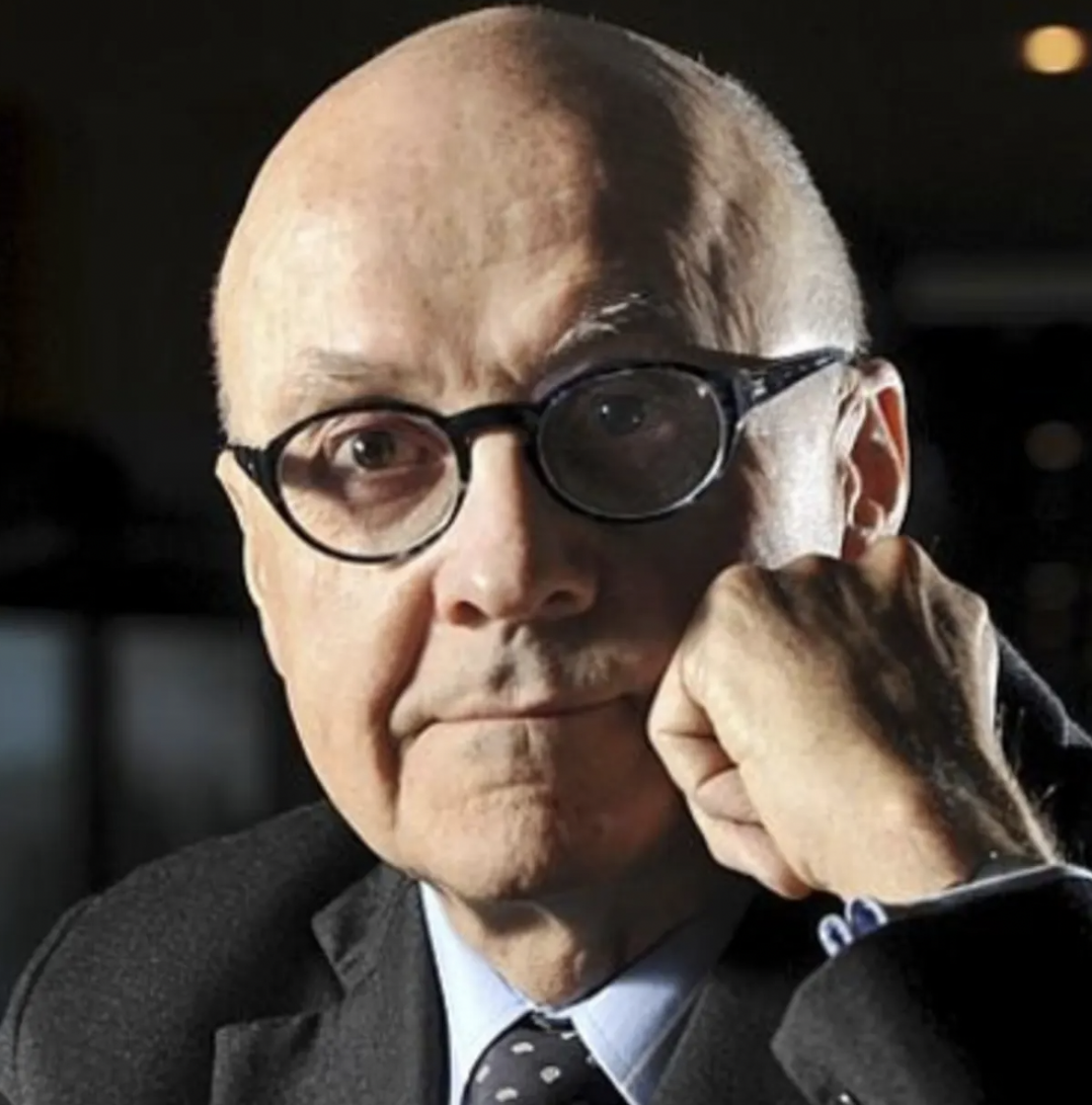

Nugget Coombs, who was one of Australia's most influential public servants in the 20th century, was a key architect of the policy.

In 1944, he gave one of the first public explanations of what full employment could look like when he delivered the Joseph Fisher lecture at Adelaide University.

The title of his lecture was "Problems of a high employment economy."

In that talk, he defined full employment as a "high and stable level of employment" that would see "a few more jobs available than men and women to fill them."

He said full employment would tend to "a slight but persistent shortage of labour" (my italics).

But it wouldn't mean everybody would always have a job, either.

Why? Because some people don't have to work. Some people can't work (due to illness and disability). Others need time to move from one job to another. Some prefer seasonal jobs. And there will always be some unemployment as industries or occupations decline and new ones emerge.

But even accounting for those realities, he said full employment would see far more people in jobs than existed in the wasteful inter-war years, when 10 per cent of the workforce was frequently without work.

And at that stage, he envisaged full employment looking something like 4 per cent of men, and 2 per cent of women, who were seeking jobs being unemployed at any moment.

But a few years later, after full employment had become official policy, the unemployment rate fell to 1.2 per cent in 1947 and to 0.9 per cent in 1948.

Australia's long period of very low unemployment had begun.

Full employment had many dimensions

However, that low unemployment rate was just one aspect of full employment.

It's easy to forget today, but the original policy was embedded in a larger framework of whole-economy welfare.

And there are two points to make about this.

First, Coombs and his colleagues believed full employment should be supported by an Australia-wide employment service sitting at its centre.

That service would act like a centralised labour exchange: it would inform job seekers of any vacancies around the country, and it would let employers survey the entire field of available labour.

That's why they established the Commonwealth Employment Service (CES) in 1946, to render services to that end.

So, a crucial element of "full employment" was the institutional support that came with it.

Second, the full employment policies weren't narrowly focused on helping people find jobs and keeping them employed. They were also concerned about the welfare of unemployed people and their families.

Coombs and other architects of full employment had painful memories of the Depression, with its high rates of poverty and destitution.

That's why he finished his 1944 lecture by arguing that Australia shouldn't return to its pre-war economy, "where the shock absorber for the vagaries of the economic system is the health, happiness, and lives of human beings."

The full employment framework acknowledged that unemployment wasn't the fault of the unemployed.

But what about a more confident work force?

Now, Coombs knew that some people in the community would dislike full employment.

Why? Because it could make workers harder to control. If jobs were plentiful, workers may get choosy.

"In the past labour discipline was based primarily upon the threat of dismissal, with its consequent fear of unemployment," he said in his 1944 lecture.

"If that fear is removed there may be reduced output, increased labour turnover, absenteeism, and so on."

However, he said employers and policymakers should be smart enough to figure out different ways to instil labour discipline, rather than relying on mass unemployment.

"We cannot expect to transform the basis of labour discipline overnight after a hundred and fifty years during which it was based essentially on a threat," he said.

His observations were similar to those of the Polish economist Michał Kalecki, who in 1943 predicted there'd eventually be a backlash from the business community to full employment policies.

"It is true that profits would be higher under a regime of full employment than they are on average under laissez-faire; and even the rise in wage rates resulting from the stronger bargaining power of the workers is less likely to reduce profits than to increase prices, and this adversely affects only the rentier interests," Kalecki said.

"But 'discipline in the factories' and 'political stability' are more appreciated than profits by business leaders," he said.

What about full employment in modern times?

But fast forward to today, where full employment means something very different.

Things began to change in the 1970s.

When Australia's economy was hit by "stagflation" in the 1970s, and the unemployment rate jumped to double digits, policymakers abandoned their old commitment to full employment amid the chaos.

They embraced a new theory that said higher levels of unemployment may be "natural" for prevailing conditions.

And they adopted a new definition: full employment would mean the level of unemployment that kept a lid on inflation (that is, that stopped wage pressures and prices growing too quickly).

That meant the economy could apparently be in full employment when the unemployment rate was 4 per cent, or 6 per cent, or 8 per cent or higher.

It depended on conditions.

And that's what full employment still means today, when you hear policymakers referring to it.

When modern central banks lift interest rates to dampen inflation, they know the trade-off could be higher unemployment. It means unemployment is being used as an inflation shock absorber.

But we've also changed the institutions that support full employment today.

Policymakers slowly dismantled the Commonwealth Employment Service after the 1970s, with its "employment services" being privatised in 1998.

That privatisation has proven very profitable for the private companies that win lucrative government contracts to deliver those "employment services" each year.

But it's also created a system in which unemployed Australians are getting trapped inside a punitive system of "mutual obligations" that feed the profits of the private providers.

Despite Coombs' warnings in 1944, we've deliberately pivoted back to a situation "where the shock absorber for the vagaries of the economic system is the health, happiness, and lives of human beings."

We're experiencing over-full employment?

So where does that leave us?

At the moment, economists who use the mainstream model say we're actually below full employment, if you can believe it.

That means they think there are more people employed than is sustainable for current conditions, and it's contributing to wage and price pressures and labour market inefficiencies.

They say the unemployment rate will eventually have to rise again.

It feels like a lifetime ago now, but in the Morrison Government's final budget in March, Treasury officials were forecasting the unemployment rate to fall to 3.75 per cent in the September quarter (we're now at 3.5 per cent).

They also assumed the current level of "full employment" was an unemployment rate of 4.25 per cent, meaning we're now experiencing over-full employment.

From an employer's perspective, that may feel right. Some employers say it's harder than it has been for years to find suitable workers.

And labour markets are relatively tight.

The employment-to-population ratio, and the participation rate, hit fresh record highs last month. Part-time jobs are being converted into full-time jobs. The youth unemployment rate (15 to 24 years) has fallen to 7.9 per cent, the lowest since 2008.

But there's also a lot of noise in the system.

Even with such tight labour markets, most workers aren't seeing their relative scarcity reflected in higher wages — real wages are still slipping backwards.

Workers are suffering such high levels of illness that absenteeism has become a major issue, and the Albanese Labor government is having to be shamed into extending COVID relief payments to affected workers.

And we still have millions of Australians living below the poverty line, with thousands caught in a punitive unemployment benefit system that needs reforming.

So, this may be the closest we've come to full employment in the neoliberal era, but it's not what full employment was supposed to mean.